In the summer of 1996 I arrived in Kampala aged 21. I’d spent the three months previous working in Israel on a kibbutz, had then dropped back to the UK for two days to meet up with a university friend, Flora, before we launched off on a year of teaching in Uganda. Last Friday, I returned to Kiboga, on the back of a week of work in Entebbe, and I re-lived as much of my year as a teacher there 20 years ago as I could squeeze into 36 hours…

As Flora and I walked out of Entebbe airport’s arrival terminal for the first time, back in 1996, and breathed in the fragrant dusty wood smoke that was to become a natural home for each of my senses for the year to come, I felt an innocent abandon about what lay ahead.

It was as if all I had known before then disappeared in that moment.

We arrived later in the night in the district of Kiboga, north west of the capital, deposited in an instant out of the side of a battered up matatu taxi, which had miraculously weaved its way unhinged over pot-holed dirt tracks for the previous four hours.

It was pitch black as we stood there on the roadside with Nathan Mayanja, a decorated local leader with whom I was to forge a twenty year friendship, and who had accompanied us from the airport.

I could feel the heat of adrenaline about what was in store next. The wood smoke scent was thicker here, and there was a constant procession of lumpy shadows and bike headlights bobbing past, as a flow of passers-by went about their evening bustle.

That first night, Flora and I were to tick off a number of “firsts”. Pit latrines – or “long drops” as we knew them – for starters, but also bathing from a washing up bowl with a bar of blue soap, sleeping under a mosquito net, drinking about a litre of warm Nile Special beer out of the bottle (and with a straw) and that feeling, as you lay down and closed your eyes to a chorus of grasshopper percussionists, that this was like nothing you had ever experienced before in your life.

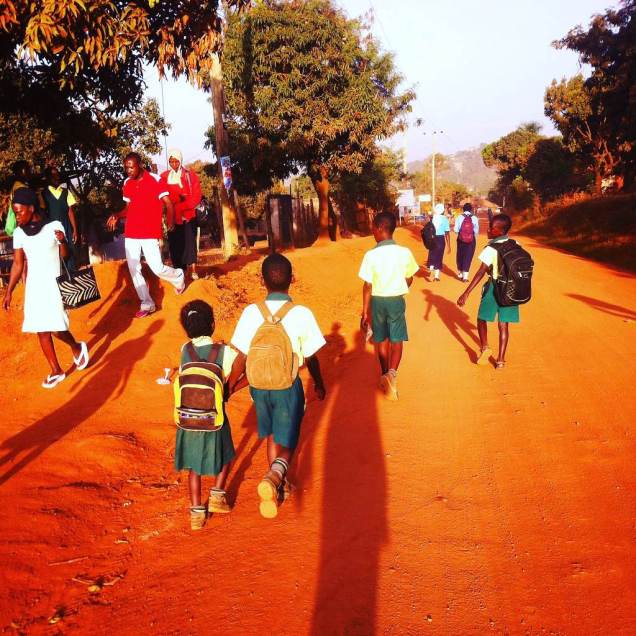

This weekend, re-visiting the two places at which I spent my year as a teacher (the first one pictured above), meeting village leaders, bumping into old acquaintances, and returning to the schools at which we taught back then, I was spell-bound at being back…

…at one point, I even managed to knock on the door of an old friend called Jane, and almost gave her a heart attack at the sight of my pale ‘musungu’ skin beaming straight up at her.

I also got to stay with Nathan for the night, his son Michael chaperoning me as Nathan had done in 1996.

We visited various family members of theirs, including Nathan’s sister and brother-in-law – Mary and John – on my way to the airport (as has been the tradition on each of the three visits I’ve made since I left in 1997). We sat on their balcony in Rugaba, sipping beers and laughing and joking about as many topics as you can imagine covering in three hours.

It was a rich slice of the past and, sat here in a restaurant in Singapore a few days later, on the eve of a conference commitment I have, I cannot believe it all actually happened.

All I can say is that life in Uganda is one of resilience.

Whilst Kampala, in 2016, offers anyone with cash so many of the modern pleasures for which Ugandans have patiently waited for decades, the throng of the capital’s citizens (Uganda is the fourth fastest growing population in the world currently) are hard at getting through another day of raising “some little money”.

The markets are frenetic and the taxi park’s chiseled “hawkers” haggle for cents a time, as they go from person to person, selling biscuits, sodas and leather belts.

In addition to the bars, cafes and nightclub scene that keeps Kampala abuzz, other notable signs of change were plain to see. Shopping malls, roads jammed with vehicles, and every other outlet selling mobile credit and smart phones.

Downtown, the old buildings I recall, such as the sacred confines of the main post office (from which I used to send a fax home and buy stamps for my airmail letters) are seemingly unchanged. Enormous crested cranes still sit atop the high rises, swooping down onto the manicured lawns of the Sheraton hotel – our small oasis in 1996 for expensive coffees and porcelain bathrooms.

In Kiboga, too, life seems much the same as it did twenty years ago.

The road there might be tarmac now, and the addition of new dwellings and guest houses (along with an internet café) certainly promotes a veneer of change, but most people are struggling on as before. Trying to save just a bit of money to repair their roof, or extend their houses, make the school fees payments, or buy a second cow.

As I moved about in Kiboga last Saturday, the thousands of surrounding acres of dark green and copper orange banana fields, which envelope the rural parts, sway and bake in the sun.

It is as if they are winking back at you when you stare too long, reminding you of who is actually in charge here – Uganda is a bread basket of organic food, but matooke (steamed banana) is king. It is eaten as a staple for breakfast, lunch and dinner. In culinary terms, matooke is omnipresent, plopped on your plate at each and every meal.

As Nathan’s son Michael explained to me, and knows too well, Uganda is changing but its people in many ways are still frozen stuck in culture, traditional, politics and life as they have always known it.

Michael himself is stopping at the four children – Jane, Bob, Sam and baby Robina – he now has. This is already too many in some ways. Nathan, his father and 70 years old next year, now has 12 children himself (his youngest is 3 years old). And, if you want to keep on the subject of informal data collection, I learnt that Nathan’s brother-in-law, John, is one of 30 siblings. His own father is alive today at 99 and was still adding to the population in his late 70’s.

“This is the African way,” John tells me. John, and his wife Mary, have three of their small grandchildren at home with them these days, as some of their own kids are overseas working – “it’s what we do,” they tell me, “it’s our culture”.

My heart broke several times in this short trip down memory lane.

One of Nathan’s sons, Raymond, cannot walk, after falling out of a mango tree aged five, and he sits all day long in a ramshackle room in Kampala. We visited him twice – he is in his late twenties now – and also checked in on Bob, Michael’s second son, who is 15, staying in Kampala also, and who suffers epilepsy from malaria he caught as a child.

Like Raymond, Bob hasn’t been to school either, as a result of his condition, and his family are scrambling to find money to get better medical support for him.

Bob wanted to come with Michael and I to the airport, but he wasn’t allowed. He wants, of course, to be back in the village with his family, but sadly this won’t happen for a while.

The cold and stark realities of Ugandan culture, when it comes to kids and their place in the household hierarchy, (at the bottom) is a thousand miles away from what I know.

Yet, it also feels like another striking example of the resilience that is imbued in Ugandans from the time they take their very first breath. What the future holds for Raymond, for Bob, and for others like them, is hard to predict. ‘Struggling on’ is, perhaps, their only option.

All I do know, for certain, is that I will keep coming back here for as long as I can. As I told Kiboga’s village council leaders on Saturday: “Uganda will always have a place in my heart,” and I really meant this.

However, inevitably, when I do return again and again, each time I imagine I will try to make sense of Uganda – its past, as well its rapidly evolving present realities.

And I’ll reflect on these, I have always done, with both immense privilege and joy, as well as with confounded confusion and a sense of shame.

This is a very moving and thought provoking piece, Tim. Twenty years is a long time ago but I remember so well your “letters from Kiboga”, that took ages to get back to the UK, and our fortnightly brief telephone conversations arranged through Mabel in the Post Office who was in charge of the single telephone line into the village. Things change, but clearly the people don’t. It must have been an emotional experience for you – thank you for sharing it. POPS