This week I spent three days up north in Ba Vi National Park for a work gig, facilitating a group of organisations preparing to launch a sizeable programme to support both local communities and local wildlife.

Several participants were environmental specialists and turned up with cameras boasting enormous zoom lenses in camouflage casings, plus tripods, binoculars, and the enthusiasm of people who know exactly what might be hiding in the next tree.

Our training room looked straight out over the forest canopy. Every so often we paused mid-discussion so one of the pros could point out a flash of wings, or rare birdsong drifting through our windows.

“What a privilege”, I offered to the group, for us all to be gifted that time together, and in those surroundings. And it really was.

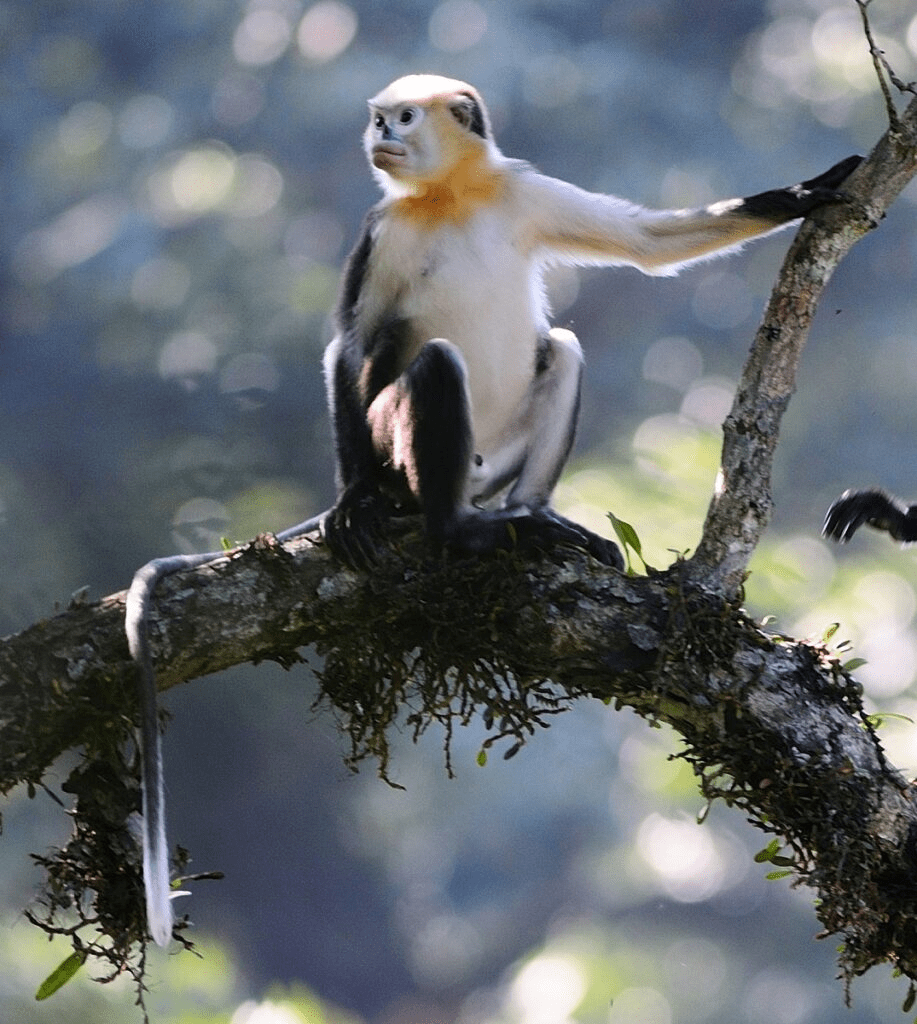

Vietnam, historically a place where biodiversity losses have been severe, has been investing far more in conservation in recent years. Some species here exist nowhere else on earth. The Tonkin snub-nosed monkey, for instance, lives on in a single province. The most recent census estimates around 250 adults remain.

One of our colleagues last week, from Flora and Fauna International, is a global orchid expert who has photographed 100,000 of them, and gives regular keynote speeches about orchids around the world.

He explained how local rangers and conservationists are fighting to protect the Tonkin. Hearing about the level of care, energy, and sheer patience involved was humbling and inspiring.

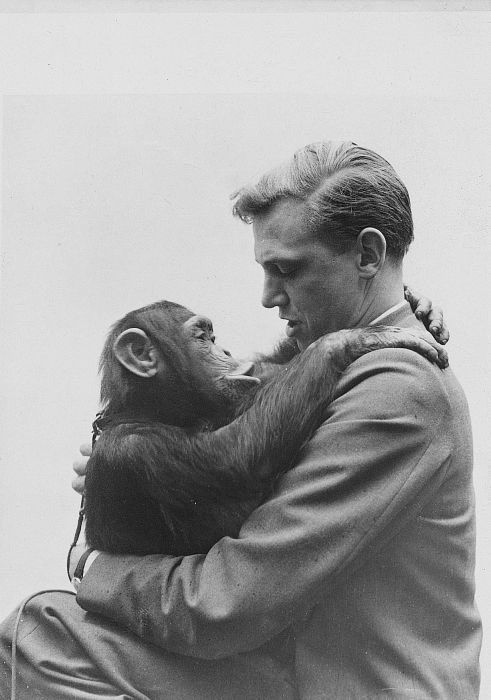

It also brought me back to a recurring question: just how would I describe Vietnam’s cultural relationship with animals after fifteen years living here?

It is, in truth, a study in contrasts.

On the one hand, conservation campaigns are growing, park systems are strengthening, and young people increasingly speak the language of biodiversity, sustainability, and stewardship.

On the other, daily life still carries a kind of blunt, transactional way about it.

The morning “wet” markets offer a menagerie of protein options. Fish are sold alive from tubs of water, and dispatched on the spot after being clattered with the back of a knife and scaled while still flapping, before being plopped into a plastic bag for the customer.

Frogs sit bound in twine, together in pairs, until sold, when they are abruptly sliced open and their skin pulled off like a wooly jumper being removed.

Every part of a pig is eaten. Colleagues of mine used to bring the ears to work for lunch. Once I’d overcame the mild shock of seeing a pig’s ear next to the sugar jar in the office kitchen, it dawned on me that there is something genuinely honourable in respectfully consuming all the parts of an animal.

In so many other scenarios around the world, millions of animals are treated inhumanely, week on week, slaughtered at industrial scale levels, their body parts packaged in aesthetically pleasing ways, and half of their carcasses thrown away.

And yet, emotional distance can drift into callousness, and there is still a rather cruel vibe to how certain animals are treated here – although, as always with cultural norms, one person’s cruelty is another’s everyday practicality.

I’ll never forget taking my friend Maude to dinner in 2012 at a rooftop BBQ in Saigon. I accidentally ordered a dish that involved a glass bowl of cold water being placed on a stove in the middle of our table, and a handful of live prawns being tossed in. As the water warmed to boiling temperatures and they began scrabbling at the sides, we found ourselves staring at the bowl in disbelief, even as other diners treated it as a normal Tuesday night.

The momentum toward conservation in Vietnam is tangible. New interventions now prioritise biodiversity and environmental guardianship in ways that simply weren’t part of development work fifteen years ago.

Being up in Ba Vi, especially knowing how severe Hanoi’s pollution has been lately, reminds one that nature is sacred – and that our newfound concern for ecological impact is, historically speaking, breathtakingly recent.

Maybe that’s why birdwatching is exploding globally. People want to admire something beyond themselves. They want a reason to look up in awe.

And yet our attention is fragile. Life distracts. Work distracts. Ego distracts. As I wrote last week on the anniversary of Rosa Parks’ arrest, we easily get tangled in our own “stuff” and lose sight of the bigger tapestry we’re part of – the birds, the bees, and each other.

On my flight back to Saigon this evening, I watched a documentary about David Attenborough’s life. As always, in admiration of the colossal effort he’s put in over sixty years to hold up this one truth – that we so willfully seem to forget – which is, very simply, that we’re living in unprecedented times.

To quote Attenborough:

“We are currently in the midst of the earth’s sixth mass extinction, one every bit as profound and far-reaching as the extinction of the dinosaurs.”

Watching the great man and orator in the documentary, mic-dropping as he has done at COP conferences, Davos, and the like for the past twenty years, was a timely reminder of how to better see the relationship we have with nature.

While climate change and global warming frame how we impact nature, of course it is our fragility, dependency and ultimately our sustainability which relies so heavily on the health of the natural world.

Each drop of water and gulp of air is because of nature, not government or big business. And each time another species sits on the brink of extinction, we are stepping that bit closer to the day when it will be our turn.