Saigon Diary: Jan 13th, 2026.

We’ve been back in Saigon for exactly a week now, in the space of which we’ve experienced pelting rain, pollution-clogged air, baking afternoon sun, and the coldest temperatures in ten years (17 degrees).

Over in Australia, where we spent Christmas, the country has seen some of the most prolific and deadly bushfires in recent memory.

In the UK, there was a cold snap this month, momentarily freezing not just people’s water pipes but their ability to go about their day-to-day business, hounded as they were by news outlets preaching Armageddon warnings about sealing windows and purchasing extra toilet paper.

The topic of the ‘the weather’ is a universal ice-breaker (pardon the double meaning) casually interrogated daily by everyone. And yet the signs couldn’t be clearer: we’re teetering on the edge of permanent humanitarian fragility.

These ever-mutating climate threats should be enough to alert us to the impending quagmire of turmoil that awaits us round the corner – country to country, there will be no exceptions – and we should be braced for more, not less, disruption. But we often pretend to ignore the symptoms (I’m guilty of doing that constantly).

Obviously the ability to survive in the future will largely tilt in favour of those with money.

If you’re reading this, then you’re already in the top echelons of society when it comes to being “comfortable”. Like me, you perhaps might “care” about climate change, but that isn’t going to stop you booking flights back to see your family in the holidays.

The current impacts of our warming planet are stark, and the issues chase at our heels like a snappy terrier.

The truth, of course, is that this pesky dog is easy enough to muzzle if you can afford it.

******************************

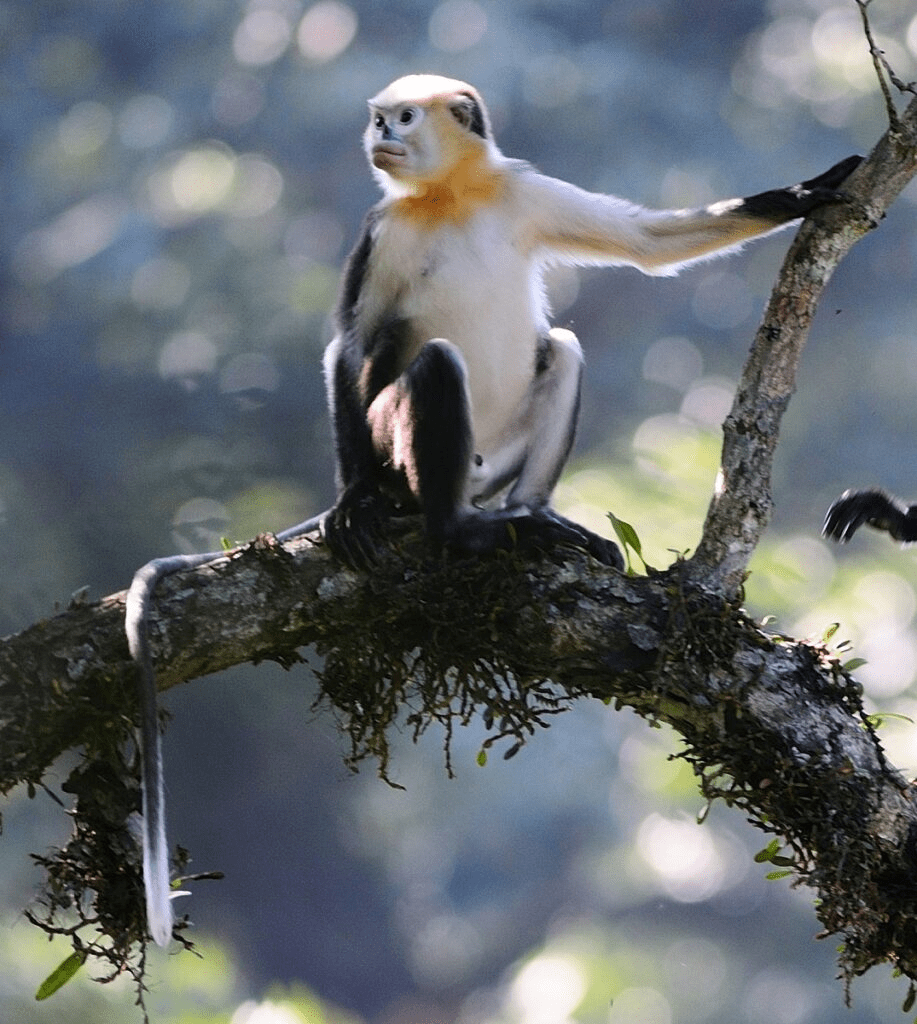

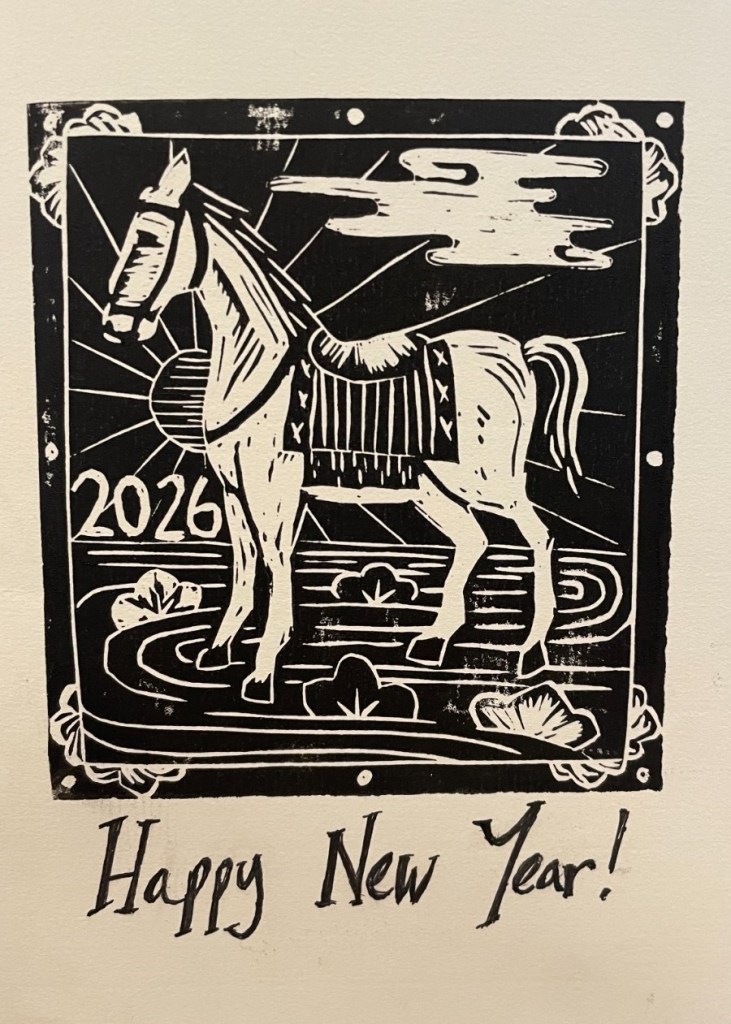

Meanwhile, Chinese New Year is approaching over in this part of the world, and the Vietnamese are in countdown already.

Office outputs across Saigon are running on the faintest wisps of enthusiasm, as locals traditionally use the western festive season as the starting pistol to their own run up to what they call ‘Tet’.

New Year’s Day this year is late – Feb 17th – and it’s also a fairly prestigious one (the Year of the Horse) which means the excitement and build-up to the event itself is extra punchy.

For the Chinese, the Horse symbolises strength and vitality – the saying goes that “success arrives on horseback”. That’s enough, by all accounts, to merit this particular year one of the more popular for having children. Hospitals and schools routinely re-organise their resources to accommodate this reality: more babies are born in an auspicious year, meaning more children going to school further down the line.

Much like how we traditionally herald in the birthday of Christ, Tet customs are anchored in family and in catering.

Where some of us celebrate annual turkey culling in time for December 25th (complete with other foods and drinks we simply don’t touch again for the following 364 days – Brussel sprouts, bread sauce, mince pies, Eggnog etc) over here during Tet there will be millions of sticky rice cakes, pickled vegetables and braised pork and eggs curated and consumed.

The locals will meticulously tidy their houses prior to New Year’s Eve, hand out “lucky money” to children, and spend time worshipping their ancestors.

In contrast, for most Brits anyway, attention to the tidiness of one’s house often slips for a week or so during Christmas. Instead, decorations clutter the walls, living rooms are carpeted in discarded wrapping paper, and emergency chairs, you didn’t even know your parents owned, are deployed to seat guests and “blow-in’s” who might materialise at the mere prospect of being offered mulled wine and a honey mustard chipolata on a cocktail stick.

******************************

I’m fast approaching my fifteenth anniversary of living in Saigon, and in spite of a longing to be rugged up outside in the English cold, clutching my fingers round a hot drink while listening to carols and losing the feeling in my toes, the charm of Vietnam at this time of year oozes out of everyone you meet.

From shopkeeper to security guard, folks are mildly giddy at the prospect of Tet as it means they’ll also receive their “thirteenth month” bonus, will soon be spending time with their loved ones, and generally getting caught up in all the festivities.

As I think back to the mercurial weather we’ve had this last week, and look at the topologies of this country – the rising sea levels, the low-lying villages in the Mekong, the seasonal flooding up in the centre of Vietnam, and so on – it seems inevitable that any future solutions to safeguard communities to climate shocks are up against all odds.

There are simply too many vulnerable people in the country. There isn’t the infrastructure – yet – in place, nor the funds to fast-track technological solutions.

Which makes the act of celebration, on the national scale that Tet demands, all the more poignant.

This year, by hook or by crook (and while I can’t stop riding my spluttering motor-bike around town, and will inevitably end up flying here or there) I will endeavour to be more committed to supporting local organisations and efforts to turn learning into practice, when it comes to the environment.

Even if that, for today, is just to be writing about it and sharing my thoughts into the ether.

The organisations that are working on climate issues here are still nascent. But there are a growing number (I wrote about some of them in December who I met up north). They need more recognition and more funding. They need to collaborate wider.

If you would like to recommend any to me, or would be interested in learning more about those currently in operation, then drop me a line and I’d be happy to connect.

Until next time!