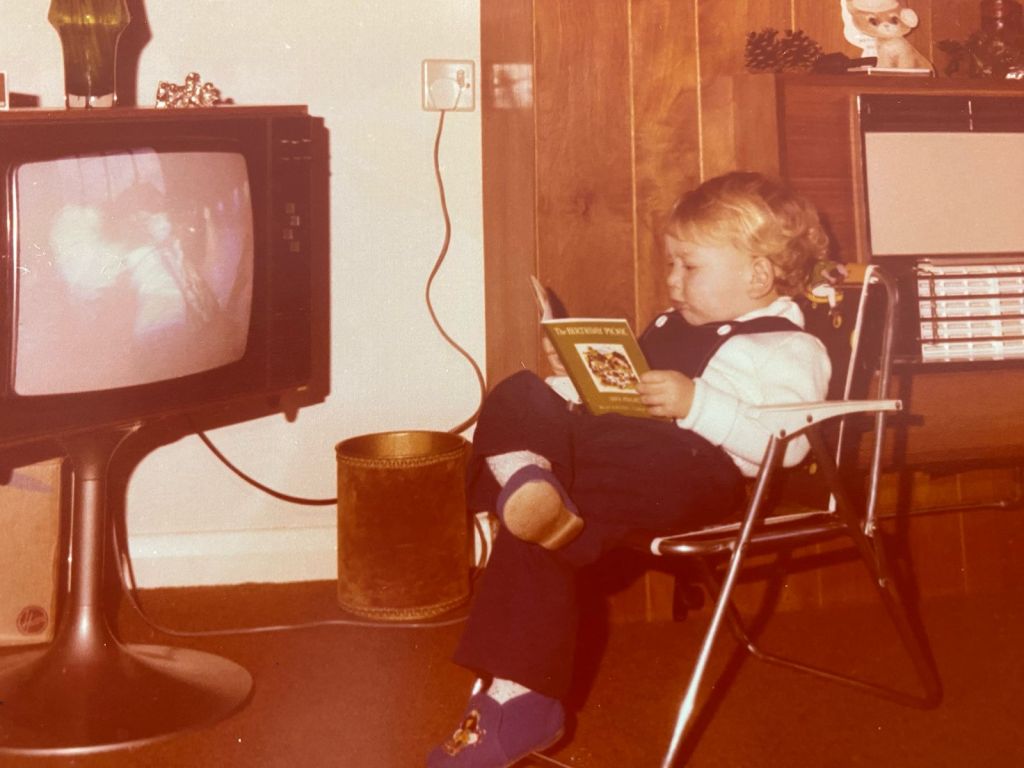

I came into the world a bit tangled, with the umbilical cord wrapped tight around my neck, gasping for air. My first act then being to terrify my parents, before nurses whisked me off to the emergency room.

Three days later, I was issued a birth certificate. It was dated 30th April, 1975 — the official date of the end of the American-Vietnam War.

Up until quite recently, I would have had a hard time confidently locating Vietnam on a map. I didn’t grow up thinking much about it, and was too young to have witnessed the street marches and anti-war protesting. Vietnamese cuisine (now found on plenty of city corners the world over) hadn’t reached UK high streets in the 70’s and 80’s.

For me, the story of that War was told through watching Hollywood movies, rather than it unraveling in real time as it had for my parents, in pixelated black and white TV footage of American GIs and the devastation caused by Agent Orange.

Vietnam, therefore, never felt personal to me, as I meandered through my twenties and half my thirties working for non-profit organisations in London dreaming, instead, of returning one day to Africa.

Fast forward to 2009 and 2010, and I took a few work trips with CARE International to Laos, Cambodia and then to Thailand. Visiting projects and speaking at conferences. My first real immersion into a part of Asia that was soon to become my home.

By February 2011 I’d arrived in Saigon on an 18-month secondment. We chose a kindergarten for our two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Florence, the day after landing and had picked out an apartment — in ‘River Garden’ — by the end of the first week.

Fourteen years on, and Flo is about to sit her GCSEs out here, while her younger sister, Martha, spent last week performing in a high school musical.

I re-married just before the outbreak of COVID-19, and me, Issy and the girls enjoyed seven years living in our family home, not far from where I’m writing this now.

In February 2023, we moved back into River Garden. We’d come full circle.

On the pages of this blog site, I’ve tried to capture the ups and downs, the ingrained moments and experiences, that living in Vietnam has scored into the archives of our memories. This is my 160th post on Saigonsays.

Some days, I still marvel at how a temporary posting turned into a life. How the place I’d never imagined for myself became the very platform from which I’ve launched myself, day after day, for so many years.

I wonder about those last American helicopters, pitching off what is now called “The Reunification Palace”, taking their passengers to begin the next stage of their lives while, many miles away in England, I would have been sleeping, my breathing finally calmed, curled up in the safety of my mother’s arms.

Over the past week, outside our 15th floor apartment windows, we’ve watched configurations of helicopters and fighter jets have been marauding around the perimeter of the city. Red flags, with the single yellow star motif, dangling below the whirring blades. These rehearsals have been going on for some time, intensifying day by day in the run up to Wednesday’s celebrations.

Last weekend, I ran through the central business district dotted with shiny red and gold floats with large posters of Ho Chi Minh hoisted high, waiting for the upcoming parades. There have been ongoing road closures, as thousands of participants are expected at the various pop-up arenas currently under construction.

Since 1975, Vietnam has become one of Asia’s most dynamic growth stories. Once reliant on rice and textiles, the country now exports everything from coffee and cashews to smartphones and semiconductors.

Industrial zones hum with activity, and foreign investment flows in through tech giants, auto manufacturers, and even renewable energy start-ups. In spite of the many immediate post-war years of poverty and crisis, it has emerged economically vibrant, particular since the US embargo was lifted in 1994.

Vietnam makes things now. And sells them to the world.

Ho Chi Minh City (still “Saigon” to many) has been a city in flux ever since I arrived. Construction cranes swing over tangled power lines. Glass skyscrapers rise beside crumbling French villas and wartime relics. The city’s long-promised metro line opened at Christmas and, so far, seems to have a steady footfall of passengers.

Grab bikes are taking on the traditional xe ôm scooter taxis, and once-sleepy alleyways (“hẻms“) like where our old house is nestled, are now home to craft beer joints and co-working spaces.

Culturally, I’ve noticed some shifts, too. Once more closed and conservative, today’s Vietnam pulses with creative energy. Indie music scenes are growing in Hanoi and Saigon. Young designers are reclaiming áo dài silhouettes in streetwear collections. Rooftop raves, contemporary galleries, experimental film screenings — they’re no longer underground, but part of a new, confident generation.

Many returning second (and third) generation Vietnamese are here to claim their stake in a market that is primed for more growth yet. These returnees’ (“Việt kiều“) represent business owners and entrepreneurs who are globally aware, yet deeply rooted. They are inevitably more digitally fluent also, curating a fascinating new norm here, sometimes through Instagram, sometimes in makeshift studios, or simply from behind laptops in noisy cafes.

Talk of the War is limited. The museums still draw tourists, and the Cu Chi tunnels remain a rite of passage where you can walk through the tunnels and get a visceral sense of the war’s intensity. Visitors can even fire rifles on site. A somewhat a surreal experience, where trauma meets tourism.

If arriving in Cu Chi by boat, you’ll get to glimpse the fragile backwaters still skirting the city. I’d encourage anyone traveling here to take to the waterway systems. It’s a reminder that, despite the optics of growth, much of Vietnam’s life remains delicately balanced.

Over my years here, I’ve met several people who fled Saigon in the late 1970’s. Some on boats, aged three or four, but still with early recollections of the part their families played in history. With so many since returning from far-flung cities like Melbourne, Houston, Toronto, and Paris, Vietnamese identity now stretches not only across continents, but also across generations.

Today, America is one of Vietnam’s largest trading partners. There has been military cooperation, as well as significant tech investments over recent years. Thousands of Vietnamese students flock to U.S. universities each year, and five U.S. Presidents have visited since 2000, starting with Bill Clinton’s historic trip to normalize relations. Obama’s 2016 visit lifted the arms embargo, and the humble plastic table where he and Anthony Bourdain shared bun cha and beers in 2016 has been preserved behind glass.

I remember too, ten years ago, for the country’s 40th anniversary celebrations, that the streets were lined with posters displaying the livery of many American brands, such as Dunkin’ Donuts and Domino’s Pizza. Slews of of McDonalds and Starbucks franchises have been around since then also, showing no sign of easing up their steady expansion.

Two nations, once at war, appear to now be walking the same economic and strategic tightrope, cautiously, but in step. And, whilst I’m no economist, it feels like the government here often balances very well its relations with America and China, respecting the traditions of its political past and commitments to all its citizens, while also aiming high to be a serious contender on the world stage.

Others would agree on this. Matthew Sayed writing in the Sunday Times last week, reflects on his ten-day journey through Vietnam, observing a nation propelled by a vigorous work ethic and a forward-looking mindset. He feels these characteristics, along with the country’s impressive economic growth rate, contrasts with what he describes as an “internal decline” in the West.

I suspect there are arguments here both ways, but Sayed’s weighing up of the West’s “obsession with past grievances” alongside Vietnam’s “determination and resilient outlook on the future” strikes a chord.

Do Western leaders currently have the mettle, along with the strategic vision, to deal effectively with crises?

Perhaps that is a topic I’ll dive into soon, but certainly not until I’ve enjoyed some birthday indulgences.

So, Happy 50th to me. And to Vietnam.

April 30th is just another day. It will pass, as all days do. But it carries a weight and a wonder for me. While frantic evacuations off the top of the Reunification Palace were underway, and I was blinking up into my parents’ faces, it was fate, perhaps, that my trajectory would one day land me here: an Englishman in Vietnam.

A strange symmetry between history and coincidence.

Saigon has been the ultimate connector: where Issy and I met by chance; where we’ve built our livelihoods; and where Flo and Martha’s entire childhoods have unfolded. I’ve run through its streets relentlessly at dawn, wrestling with life’s big questions, and been fortunate to gather more than my share of good friends along the way.

I was born on the edge of history. And somehow, without ever really planning it, I’ve ended up living at its heart.